Brazil Immigration requirements

WHEN Chico Max decided to mount an exhibition of photographs of recent immigrants to Brazil, he had a harder time finding subjects than he expected. That is because just 600, 000 of the 204m people living in the country are foreign-born. The small pool of potential sitters surprised Mr Max. Nearly everyone in Brazil is descended from immigrants or African slaves; only the United States has a bigger non-indigenous population. The country’s president is the daughter of a Bulgarian; the vice-president has a road named after him in Lebanon. All of Mr Max’s grandparents came from Portugal between the two world wars. As the title of his show this month in São Paulo proclaimed, “We are all immigrants”.

WHEN Chico Max decided to mount an exhibition of photographs of recent immigrants to Brazil, he had a harder time finding subjects than he expected. That is because just 600, 000 of the 204m people living in the country are foreign-born. The small pool of potential sitters surprised Mr Max. Nearly everyone in Brazil is descended from immigrants or African slaves; only the United States has a bigger non-indigenous population. The country’s president is the daughter of a Bulgarian; the vice-president has a road named after him in Lebanon. All of Mr Max’s grandparents came from Portugal between the two world wars. As the title of his show this month in São Paulo proclaimed, “We are all immigrants”.

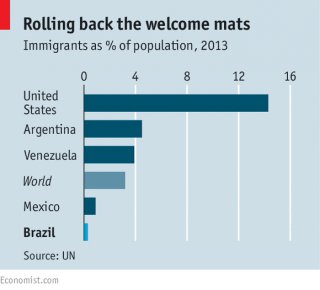

Yet Brazil’s foreign-born population peaked at 7.3% of the total at the start of the 20th century and has been dwindling ever since. It is now a fifth of Latin America’s low average and a fraction of that in melting pots like the United States (see chart). That is a problem. Brazil needs millions of well-qualified workers but its mediocre schools are not providing them. Without more immigration, analysts warn, Brazil faces a “skills blackout”.

Some of the reasons for which migrants shun Brazil are obvious. It is not a rich country (and is now facing a deep recession). Its language, Portuguese, is not widely spoken elsewhere. Yet Argentina, with a fifth of Brazil’s population and an equally troubled economy, attracts more than double the number of newcomers—about 280, 000 people a year, mostly poor labourers from other Spanish-speaking countries. They could easily master enough Portuguese to work in Brazil, although they would not solve the skills shortage.

They do not come because Brazil needlessly puts up additional roadblocks. Its legislation on immigration is “anachronistic”, admits Beto Vasconcelos, who handles the issue at the justice ministry in Brasília. The main law dealing with immigration, enacted by generals who ruled from 1964 to 1985, treats foreigners as a menace to national security and to Brazilian workers. It bars non-Brazilians from taking part in political rallies, owning stakes in newspapers or participating actively in trade unions.

It also imposes cumbersome conditions on foreign workers. Securing a work permit can take months and cost thousands of dollars in legal and administrative fees. Most work visas are tied to an employer, so changing a job requires starting the application process from scratch. Brazil’s enlightened refugee law, by contrast, grants asylum-seekers a work permit within a week of arrival, free of charge.

It also imposes cumbersome conditions on foreign workers. Securing a work permit can take months and cost thousands of dollars in legal and administrative fees. Most work visas are tied to an employer, so changing a job requires starting the application process from scratch. Brazil’s enlightened refugee law, by contrast, grants asylum-seekers a work permit within a week of arrival, free of charge.

The more qualified the immigrant, the more devilish the bureaucracy. A graduate student who wants to join a university’s faculty must reapply for a different type of visa—from abroad. A professional will typically wait a year for his or her credentials to be recognised; a yes is not assured. Few universities offer courses in a language other than Portuguese. Add to that the absence of Brazilian universities at the top of global rankings, and it is small wonder that the country hosts just 14, 000 foreign students (though beaches and an easy-going culture are a draw).

In the 19th and early 20th centuries Brazil encouraged immigrants from Europe and Japan (partly from a racist impulse to avoid further “blackening” of the population). Today Brazil, unlike Chile, does not market itself to prospective citizens.

Even when the economy is shrinking and unemployment is rising, this unfriendliness to foreign talent has a big cost. Manpower, a human-resources consultancy, recently found that 61% of Brazilian employers are having trouble filling job vacancies. Among 42 countries, only geriatric Japan, poorer Peru and tiny Hong Kong had more acute skills shortages. In an annual ranking of countries by their ability to develop and attract talent, put together by IMD, a business school, Brazil fell to 57th place out of 61 this year (from 52nd place). It scored especially poorly for security, quality of life and education.

Brazil may now be reopening a bit. The National Immigration Council, part of the federal government, has recently made it easier for students to apply for summer jobs and for some types of professional to obtain work permits for their spouses. But the council’s decisions apply to few people, lack the force of law and create a confusing patchwork, says Ana Paula Dias Marques, a lawyer specialising in migration. Since 2009 Congress has been sitting on draft legislation that would update the old law. In July this year the Senate passed a sensible version, which gives statutory backing to many of the council’s rulings. But it risks being bogged down in the dysfunctional lower house.

Alarmingly, recession, corruption and political deadlock may be pushing brainy people out of the country. Its diaspora is tiny: just 1.8m Brazilians, 0.9% of the population, live abroad, the smallest share among all countries of the Americas. But it may be growing. The consulate in Miami, the most popular destination for Brazil’s wealthy and worldly, is busier than ever. Fabriene Prudencio, who advises Brazilian parents on schools in south Florida, says business is booming. The number of Brazilian families at her own children’s (public) school in a posh Miami suburb has shot up from seven to 30 in the past six years. Several other schools have begun offering instruction in Portuguese.

Between 2008 and 2013, when economic times were still good, the trickle of immigration into Brazil became a rivulet: annual arrivals doubled to 128, 000. The newcomers, mainly from Haiti, Bolivia, Senegal and other poverty-stricken countries, provided Mr Max with his subjects. Immigrants bring cultural diversity and a go-getting attitude that characterises migrants the world over. Their faces exude dignity and fortitude. They will no doubt enrich the country. But Brazil needs more of them, and more who already have the skills that a modern economy demands.